1100 is not really prepared to hold extensive notes. 5 – Detail of Fig. 4ĭespite these add-ons, the schoolbook from c. 5 resembles the number 7 and is perhaps the Tironian note for “et”. The symbol links a remark in the margin to a specific location in the main text.

There is something special about these marginal notes: they are preceded by symbols that are the precursor of our modern footnote (more about this early practice in this post). 4 – Leiden, University Library, BUR Q 1 (c.

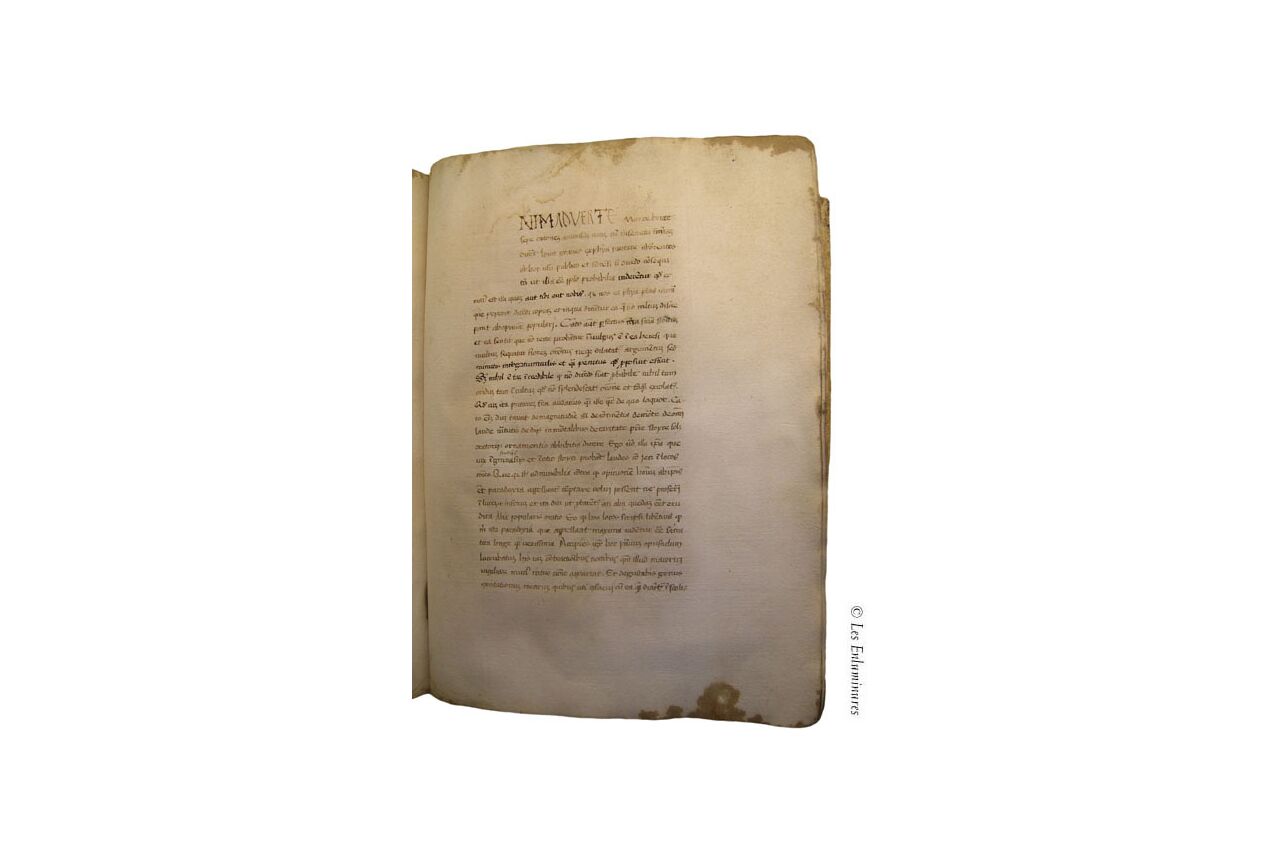

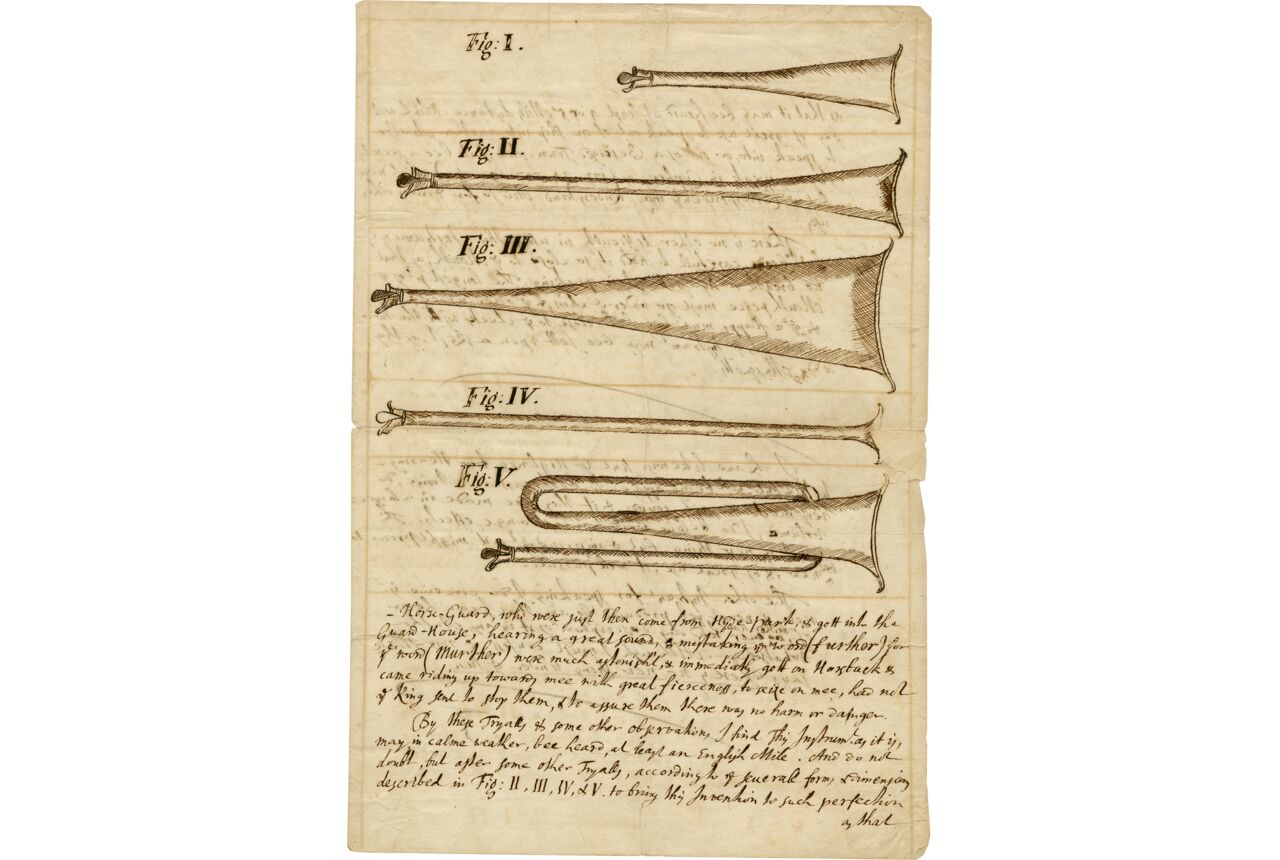

The text in the book, Lucan’s Pharsalia, was used in the medieval classroom, and it is therefore no surprise that numerous explanatory notes have been added to the text, probably by Baldwinus himself. 1100 that was donated to Egmond Abbey near Amsterdam by one Baldwinus, a teacher in Flanders. While the margin did a good job accommodating the relatively short reading aids, it could be challenging to add large amounts of text to the void surrounding the main text. Fig. 4 – London, British Library, Harley MS 3487 (13th century) – Source The student or teacher who was browsing through the book for certain information was greatly helped by these sign posts. This particular manuscript contains several Aristotle texts, which were popular in the university classroom. 4 states “Physicorum”, indicating this is Aristotle’s Physics. A particularly prominent aid is the running title placed in the upper margin. There are many other kinds of aids encountered in the margins of medieval books, including cross references to other books or locations in the same manuscript, quotation marks, labels that indicate who the quoted author is, and chapter numbers. In other words, this is a very early page number (folium number), an instrument that is apparently some two thousand years old and predates the printed book by over a millennium.

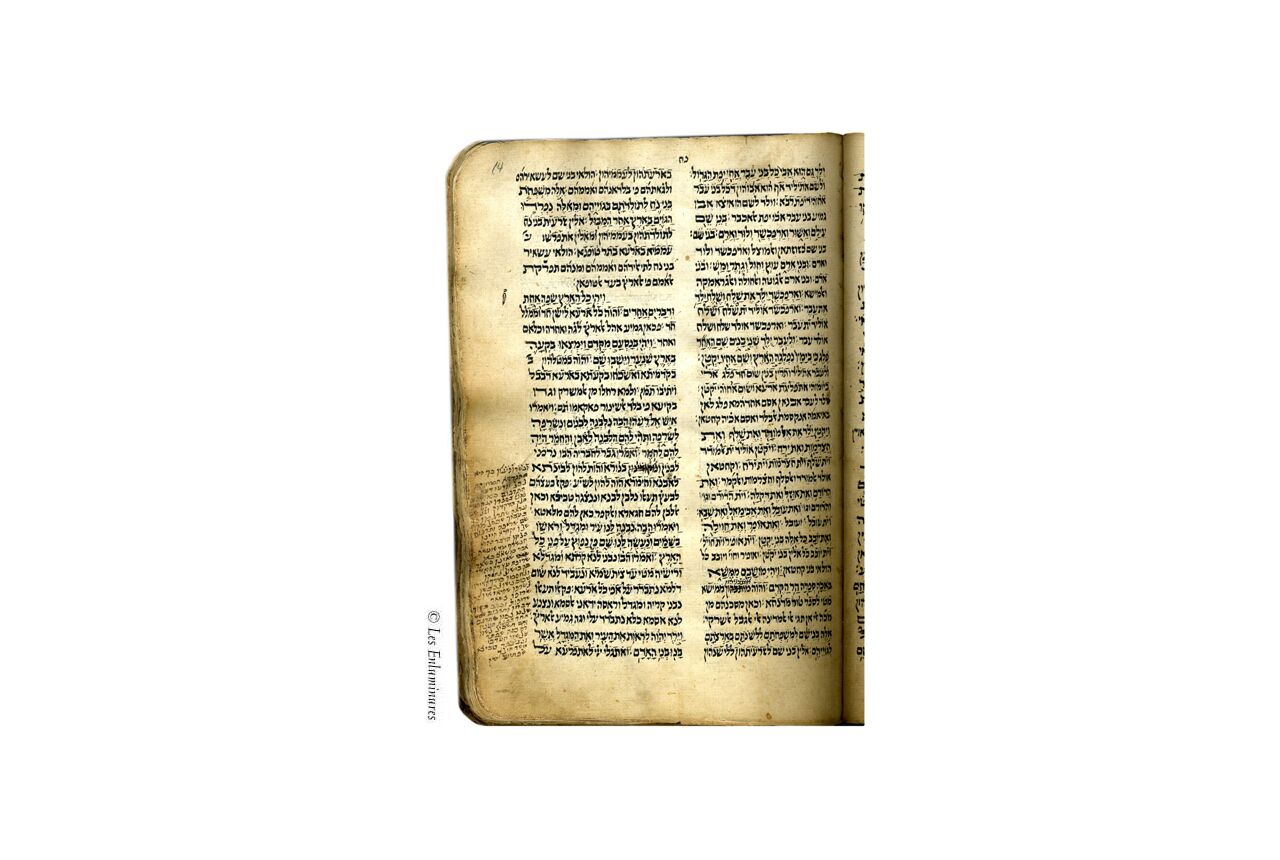

A particularly important reading aid is visible at the top of the papyrus page: the capital version of the Greek letter Mu (looking like an M), which represents the Greek number 40 (Fig. It meant that you could fill them with tools that may be helpful when consulting the book. 2 highlights that it was also convenient to have an empty space around the text. The extensive medieval margin is, in one way, simply a continuation of an older practice. While the margins have been reduced post-production through damage (the edges of the papyrus eroded), the upper margin, which is largely intact, shows how the scribe reserved ample marginal space. 2, which shows the remains of a copy of Paul’s Epistles written between 150 and 250 CE. Going back even further, papyrus manuscripts from Antiquity also included a considerable amount of marginal space. In other words, a little under half of this magnificent book is empty. A simple calculation reveals that the text takes up 58% of the page, while 42% is reserved for the outer margins. an object produced from quires (bundles of folded sheets) – came into existence in the fourth century, as discussed in my post What is the Oldest Book in the World? The pages of the famous Codex Sinaiticus, a Greek New Testament copied around the middle of the fourth century, measures 381 x 345 mm (height x width), while the text itself only takes up 250×310 mm (height x width). Medieval scribes took over a great deal of material features first introduced by their counterparts in Antiquity. The book as we know it – i.e. One answer to this question is a simple one: because this is how books were traditionally made. This implies, astonishingly, that the majority of medieval books are half empty, despite the fact that parchment was expensive and sometimes even hard to come by. My own work on the twelfth century, reflecting broader medieval patterns, shows that pages from that period consist of approximately 50% margin, although in some cases it can be significantly more. A particularly remarkable aspect of marginal space is that there is so much of it in medieval books. What a strange pair they are: words, the primary reason for the book’s existence and a vast emptiness present on all sides of the text. From the very earliest specimens produced two millennia ago, to the e-readers we use today, books contain pages that hold both text and a significant amount of blank space. Margins are both a universal and remarkable feature of books.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)